Political Culture: Values and Beliefs in Indonesia Politics – My Honest Take

JAKARTA, turkeconom.com – Political Culture: Values and Beliefs in Indonesia Politics have always fascinated me. As someone who grew up in a super diverse Indonesian neighborhood, I realized early just how much these values shaped our everyday interactions, right down to the spicy little debates about politic at family gatherings. There was a time when I thought Indonesian politics was all about who shouted the loudest, but wow, was I wrong.

Political culture— the shared values, symbols, and beliefs that shap e how citizens engage with politics— lies at the heart of Indonesia’s democratic journey. From the legacy of Pancasila to the dynamics of clientelism and grass-roots participation, understanding political culture helps explain policy choices, voter behavior, and the resilience of Indonesia’s pluralist system. In this article, I’ll define political culture, explore its Indonesian manifestations, share real-world examples, offer my candid insights, and suggest ways to strengthen our democratic norms.

1. What Is Political Culture?

Political culture refers to the collective mental models and normative frameworks that:

- Define who “belongs” in politics (in-group vs. out-group)

- Shape citizens’ expectations of government performance and accountability

- Inform the symbols and rituals (e.g., national holidays, flag ceremonies) that reinforce collective identity

- Guide modes of participation (voting, protest, clientelist exchanges)

A healthy political culture balances trust in institutions with active civic engagement, tolerance for dissent, and loyalty to democratic principles.

2. Key Features of Indonesian Political Culture

- Pancasila as Unifying Ideology

• Five principles (Belief in God, Humanity, Unity, Democracy, Social Justice) provide a moral compass and rhetorical foundation for political actors. - Gotong Royong (Mutual Cooperation)

• Community self-help projects (gotong royong) reinforce local solidarity and participatory governance at the village level. - Patrimonialism & Clientelism

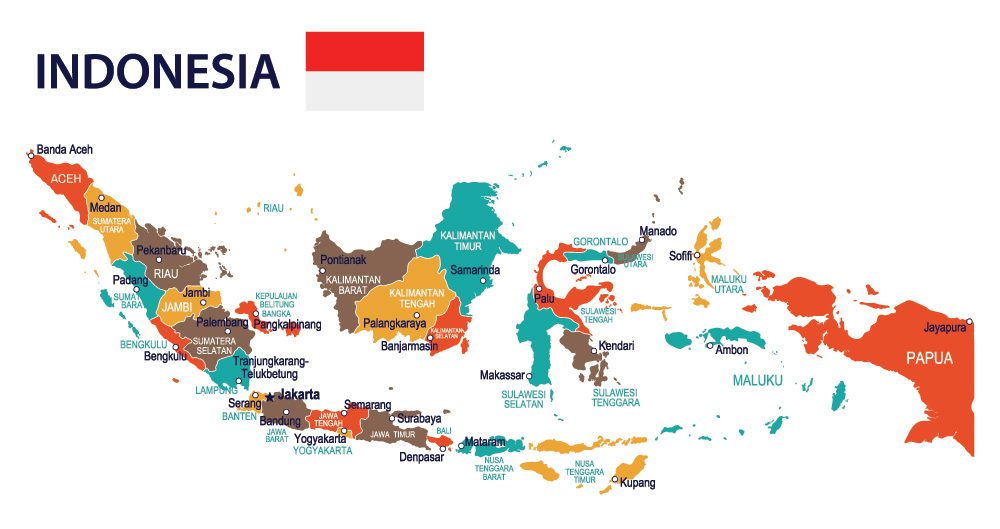

• Personal networks and patron–client ties remain strong, especially in rural areas, shaping electoral mobilization and resource distribution. - Regional and Religious Pluralism

• Indonesia’s diversity (ethnic, religious, linguistic) fosters local political cultures that sometimes coexist uneasily with national norms. - Deference to Authority vs. Activism

• Historical deference under authoritarian rule contrasts with the rise of civil-society activism post-1998 Reformasi.

3. Real-World Examples

A. Direct Local Elections (Pilkada)

Since 2005, Indonesians elect governors and regents directly. Voter turnout often exceeds 70%, reflecting high local political engagement—and sometimes intensified clientelist campaigning.

B. 2019 Presidential Election

Marked by fierce identity politics and social-media campaigns, this election underscored how religious and ethnic symbols can both mobilize voters and risk societal polarization.

C. Grass-roots Environmental Movements

In Kalimantan and Sumatra, NGOs and adat (indigenous) communities have used gotong royong traditions to defend forests—demonstrating how local culture fuels collective political action.

4. Key Lessons Learned

- History Matters

• The legacy of Suharto’s New Order still shapes deference to authority and suspicion of mass mobilization. - Ideological Frames Are Powerful

• Invoking Pancasila or religious narratives can unite or divide, depending on political incentives. - Local Variations Are Critical

• Village-level norms (adat law, Muslim boarding-school networks) often override national campaign messages. - Media & Technology Amplify Norms

• Social-media echo chambers can entrench clientelist appeals or identity-based mobilization. - Civil-Society Resilience

• Post-1998 reforms empowered NGOs and citizen-journalists to hold government accountable—yet they face new challenges from disinformation and legal constraints.

5. My Honest Take

Indonesia’s political culture is a vibrant tapestry—rooted in communal values yet constantly adapting to modern pressures. On one hand, Pancasila and gotong royong foster social cohesion. On the other, patrimonial networks and identity politics can undermine merit-based governance and inter-group trust. True democratic deepening will require valuing both national unity and local autonomy, promoting transparent competition over personal loyalties, and supporting citizens who demand accountability.

6. Recommendations for Strengthening Political Culture

- Civic Education Reform

• Integrate critical‐thinking, media‐literacy, and democratic norms into school curricula from elementary to university levels. - Empower Independent Media

• Safeguard press freedom and digital platforms against disinformation and government interference. - Institutionalize Participatory Budgeting

• Expand mechanisms like musrenbang (development planning forums) to give citizens real oversight over public spending. - Foster Cross-Cutting Networks

• Support inter-faith and inter-ethnic councils that build bridges across societal divides. - Reform Electoral Regulations

• Enforce Anti-money‐politics laws and strengthen Oversight bodies (Bawaslu) to reduce Clientelist influence.

Conclusion

Political culture is both the soil and the seed of democracy. In Indonesia, our shared values—Pancasila, gotong royong, respect for diversity—provide a strong foundation. Yet the Persistence of Patrimonialism and Identity-based Mobilization reminds us that culture is dynamic. By investing in civic education, Strengthening institutions, and encouraging genuine public participation, we can nurture a political culture that sustains accountability, Inclusivity, and national Resilience.

Sharpen Your Skills: Delve into Our Expertise on Politic

Check Out Our Latest Piece on Sentralisasi: Central Authority and National Cohesion in Indonesia!