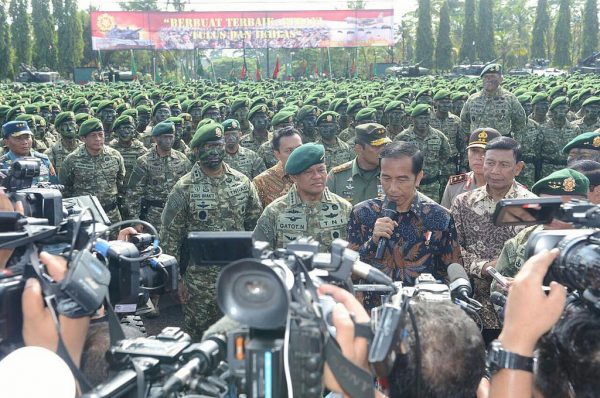

Civil-Military Relations: Understanding Power Politics Dynamics in Indonesia—Real Stories, Lessons, and Insights

JAKARTA, turkeconom.com – Civil-military relations in Indonesia represent one of the most fascinating and consequential aspects of the nation’s political evolution. From the revolutionary struggle for independence to the authoritarian New Order era, and through the democratic transition that continues today, the relationship between civilian authorities and military institutions has profoundly shaped Indonesia’s governance, stability, and development. Understanding civil-military relations in Indonesia requires examining real stories of power struggles, institutional reforms, and the ongoing challenge of establishing democratic civilian control over one of Southeast Asia’s most influential armed forces.

The Historical Foundation of Civil-Military Relations in Indonesia

Revolutionary Origins and Dual Function

Indonesia’s civil-military relations were forged in the crucible of the independence struggle (1945-1949), when the military emerged not merely as a defense force but as a political actor with revolutionary legitimacy. This origin story profoundly influenced subsequent civil-military relations, as military leaders viewed themselves as co-founders of the nation with inherent rights to participate in governance.

The concept of dwifungsi (dual function) institutionalized the military’s political role, asserting that the armed forces had both defense and socio-political functions. This doctrine shaped civil-military relations for decades, legitimizing military involvement in civilian administration, business, and politics. Understanding this historical foundation is essential for comprehending contemporary challenges in reforming civil-military relations toward democratic norms.

Sukarno Era: Balancing Act and Growing Military Influence

During President Sukarno’s rule (1945-1967), civil-military relations were characterized by complex balancing between military leaders, political parties, and the president himself. Sukarno relied on the military to counterbalance the powerful Communist Party (PKI), while military leaders gained increasing autonomy and influence. This period demonstrated how weak civilian institutions and political instability can enable military encroachment on civilian authority.

The failed coup attempt of 1965 and subsequent anti-communist purge marked a watershed in Indonesian civil-military relations. The military, led by General Suharto, emerged as the dominant political force, setting the stage for three decades of military-dominated governance. This transition illustrates how crisis moments can fundamentally reshape civil-military relations, often with long-lasting consequences.

The New Order: Military Dominance in Civil-Military Relations

Institutionalized Military Political Role

Under Suharto’s New Order regime (1966-1998), civil-military relations were characterized by comprehensive military dominance over civilian governance. The dual function doctrine reached its apex, with military officers occupying positions throughout government bureaucracy, parliament, provincial administrations, and state-owned enterprises. This system represented an extreme imbalance in civil-military relations where civilian control existed only nominally.

The territorial command structure (komando teritorial) extended military presence to village levels, creating a parallel governance system that monitored civilian populations and enforced regime policies. This structure fundamentally altered civil-military relations by embedding military authority into everyday civilian life, blurring distinctions between military and civilian spheres.

Economic Interests and Military Autonomy

New Order civil-military relations were further complicated by extensive military business interests. Military foundations (yayasan) and cooperatives controlled enterprises across sectors, generating revenue that reduced military dependence on state budgets. This economic autonomy strengthened the military’s position in civil-military relations, as financial independence reduced civilian leverage over military institutions.

Military officers developed patronage networks linking business interests, political positions, and security roles. These networks created vested interests in maintaining military political influence, complicating later reform efforts. Understanding these economic dimensions is crucial for comprehending resistance to civil-military relations reform.

Real Story: The Petrus Killings and Military Impunity

One of the darkest chapters illustrating problematic civil-military relations during the New Order was the Petrus (Penembakan Misterius or Mysterious Shootings) campaign of 1983-1985. Military and police death squads killed thousands of alleged criminals, leaving bodies displayed publicly as warnings. This state-sanctioned violence demonstrated how imbalanced civil-military relations enable military impunity and human rights violations.

The Petrus killings revealed the dangers when military institutions operate without civilian oversight or accountability. Suharto later acknowledged authorizing the campaign, illustrating how authoritarian civil-military relations concentrate power in ways that enable systematic abuses. This historical episode continues informing contemporary debates about military accountability and civilian control.

Democratic Transition: Reforming Civil-Military Relations

The 1998 Crisis and Reform Imperatives

The Asian financial crisis and subsequent collapse of Suharto’s regime in 1998 created unprecedented opportunities for reforming civil-military relations. The reformasi (reform) movement demanded democratization, including establishing genuine civilian control over the military. This transition period demonstrated how regime change creates critical junctures for restructuring civil-military relations.

Initial reforms focused on removing the military from formal political roles. The armed forces’ parliamentary seats were eliminated, military officers were required to retire before assuming civilian positions, and the dual function doctrine was officially abandoned. These changes represented fundamental shifts in civil-military relations, moving toward democratic norms of civilian supremacy.

Separating Police from Military

A crucial reform in Indonesian civil-military relations was separating the police (Polri) from the armed forces (TNI) in 1999. Previously unified under ABRI (Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia), the separation aimed to clarify institutional roles and reduce military involvement in internal security. This structural change significantly impacted civil-military relations by creating distinct military and law enforcement institutions.

However, the separation also created new challenges in civil-military relations, including jurisdictional disputes, coordination difficulties, and competition for resources and influence. The police’s struggle to establish professional identity and capacity sometimes created security gaps that military leaders cited as justification for continued involvement in internal affairs.

Real Story: The Aceh Peace Process and Military Resistance

The Aceh peace process (2005) provides revealing insights into post-reform civil-military relations. President Yudhoyono’s decision to negotiate with the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) faced significant military resistance, as many officers viewed negotiations as capitulation and threat to territorial integrity. This tension illustrated ongoing challenges in establishing civilian authority over security policy.

Ultimately, civilian leadership prevailed, and the Helsinki peace agreement ended decades of conflict. This success demonstrated that reformed civil-military relations could enable civilian leaders to pursue policies opposed by military institutions. However, the process also revealed that civilian control remains contested and requires strong presidential leadership to overcome military resistance.

Contemporary Civil-Military Relations Challenges

The Territorial Command Structure Debate

The territorial command structure remains one of the most contentious issues in Indonesian civil-military relations. Reformers argue this structure enables military interference in civilian affairs and should be dismantled or significantly reduced. Military leaders defend it as essential for national defense and disaster response, while critics note its historical use for political control.

This debate reflects fundamental tensions in contemporary civil-military relations: balancing legitimate security needs against risks of military overreach. The territorial structure’s persistence demonstrates how institutional arrangements can outlast formal reforms, maintaining military influence despite democratic transitions.

Military Business Interests

Despite reforms requiring military divestment from business activities, military economic interests persist as a challenge in civil-military relations. Military cooperatives and foundations continue operating businesses, while individual officers maintain business connections developed during active service. These economic interests create incentives for military political influence that complicate civilian control efforts.

Addressing military business interests is crucial for normalizing civil-military relations, as economic independence reduces civilian leverage while creating corruption risks and conflicts of interest. However, military resistance to complete divestment remains strong, citing inadequate defense budgets and welfare concerns for personnel.

Real Story: The Wiranto Case and Transitional Justice

General Wiranto’s career trajectory illustrates complexities in post-reform civil-military relations and transitional justice. As military commander during East Timor’s violent separation (1999), Wiranto faced indictment by UN tribunals for crimes against humanity. Yet he subsequently served as presidential candidate, cabinet minister, and chief political minister, demonstrating limited accountability for military leaders.

The Wiranto case reveals how incomplete transitional justice complicates civil-military relations reform. When military leaders implicated in human rights violations retain political influence and avoid accountability, it signals that civilian control remains incomplete and military impunity persists. This undermines rule of law and democratic consolidation.

Institutional Mechanisms for Civilian Control

Legislative Oversight

Indonesia’s parliament (DPR) exercises oversight over civil-military relations through defense budgeting, legislation, and committee hearings. Commission I handles defense and foreign affairs, providing formal mechanisms for civilian scrutiny of military institutions. However, legislative oversight effectiveness varies depending on parliamentary capacity, political will, and military cooperation.

Strengthening legislative oversight is essential for improving civil-military relations. This requires enhancing parliamentary staff expertise, ensuring access to military information, and building political consensus around civilian control principles. When parliament exercises robust oversight, it reinforces civilian authority and accountability in civil-military relations.

Presidential Authority and Defense Ministry

The president serves as supreme commander of the armed forces, providing constitutional foundation for civilian control in civil-military relations. The defense minister, traditionally a civilian position since reforms, serves as the president’s agent for implementing defense policy and managing military institutions. This arrangement establishes clear civilian authority over military matters.

However, effective presidential control in civil-military relations depends on individual leadership strength, political circumstances, and military cooperation. Presidents with military backgrounds (like Yudhoyono and Widodo) may have advantages in managing civil-military relations, though this can also blur civilian-military distinctions. The defense minister’s effectiveness varies based on personal authority, presidential support, and military acceptance.

Military Professionalism and Education

Promoting military professionalism represents a crucial strategy for improving civil-military relations. Professional military institutions focus on defense competencies, respect civilian authority, and operate within legal frameworks. Military education reforms emphasizing democratic values, human rights, and civilian supremacy help internalize norms supporting healthy civil-military relations.

Indonesia has undertaken military education reforms, including curriculum changes and international exchanges that expose officers to democratic civil-military relations models. However, institutional culture changes slowly, and traditional attitudes about military political roles persist among some officers, requiring sustained reform efforts.

Regional Dynamics and Civil-Military Relations

Decentralization Impacts

Indonesia’s decentralization since 1999 has created new dimensions in civil-military relations. Regional autonomy transferred authority to provincial and district governments, but military territorial commands remained centralized. This creates tensions when local civilian authorities and military commanders disagree about security matters or resource allocation.

Effective civil-military relations in decentralized Indonesia requires clarifying authority relationships between regional civilian governments and military territorial commands. Some regions have developed cooperative arrangements, while others experience friction. These variations demonstrate how civil-military relations dynamics differ across Indonesia’s diverse regions.

Papua and Military Operations

Papua presents particular civil-military relations challenges due to ongoing separatist insurgency and military operations. The military maintains significant presence and influence in Papua, sometimes operating with limited civilian oversight. Human rights concerns about military conduct in Papua test the effectiveness of civil-military relations reforms and civilian control mechanisms.

Addressing Papua’s situation requires balancing security imperatives against human rights protection and civilian authority. Effective civil-military relations would ensure military operations occur under clear civilian direction, with accountability for misconduct and respect for civilian populations. Progress remains incomplete, illustrating ongoing civil-military relations challenges in conflict-affected regions.

International Dimensions of Civil-Military Relations

Defense Cooperation and Reform Support

International defense partnerships influence Indonesian civil-military relations by providing resources, training, and exposure to democratic civil-military norms. Countries like the United States, Australia, and European nations support Indonesian military professionalization through education programs, joint exercises, and institutional capacity building.

These international engagements can positively impact civil-military relations by reinforcing civilian control principles and professional military standards. However, they also create tensions when human rights concerns lead to cooperation restrictions, as occurred after the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre in East Timor. Balancing security cooperation with human rights accountability remains an ongoing challenge in international aspects of civil-military relations.

Regional Security Architecture

Indonesia’s role in ASEAN and regional security cooperation affects domestic civil-military relations by shaping threat perceptions, defense priorities, and military modernization. Regional stability reduces pressures for military political involvement, while security challenges can strengthen military arguments for resources and autonomy.

Indonesia’s leadership in promoting ASEAN norms of non-interference and peaceful conflict resolution reflects civilian foreign policy priorities. Maintaining civilian control over regional security policy represents an important dimension of civil-military relations, ensuring military institutions serve rather than dictate national interests.

Lessons from Indonesian Civil-Military Relations

Institutional Reform Requires Sustained Commitment

Indonesia’s experience demonstrates that reforming civil-military relations requires sustained commitment over extended periods. Initial reforms after 1998 achieved significant changes, but consolidating civilian control demands ongoing effort to address persistent challenges like military business interests, territorial commands, and accountability gaps.

Successful civil-military relations reform cannot rely solely on legal changes; it requires transforming institutional cultures, building civilian capacity, and maintaining political will despite resistance. Indonesia’s incomplete reform trajectory illustrates both progress achieved and work remaining in establishing fully democratic civil-military relations.

Economic Factors Matter

Military economic interests significantly impact civil-military relations dynamics. When military institutions possess financial autonomy through business activities, civilian leverage decreases while corruption risks increase. Addressing these economic dimensions is essential for normalizing civil-military relations, though it requires providing adequate defense budgets and personnel welfare as alternatives.

Transitional Justice Affects Reform

Indonesia’s limited transitional justice for past military human rights violations complicates civil-military relations reform. When accountability is absent, it signals that military impunity persists and civilian authority remains incomplete. Conversely, excessive focus on past violations can provoke military resistance to reforms. Balancing accountability with reconciliation represents a persistent challenge in post-authoritarian civil-military relations.

Context-Specific Approaches

Indonesian civil-military relations demonstrate that reform approaches must consider specific historical, cultural, and institutional contexts. Models from other countries provide insights but cannot be directly transplanted. Indonesia’s unique military history, revolutionary origins, and cultural factors require tailored approaches that respect local contexts while advancing democratic principles.

Future Directions for Civil-Military Relations in Indonesia

Completing Institutional Reforms

Future progress in Indonesian civil-military relations requires completing unfinished reforms. This includes fully divesting military business interests, clarifying or reducing the territorial command structure, strengthening civilian defense institutions, and establishing comprehensive accountability mechanisms. These reforms would consolidate civilian control and professionalize military institutions.

Building Civilian Capacity

Effective civil-military relations require capable civilian institutions that can formulate defense policy, exercise oversight, and manage military affairs. Strengthening parliamentary defense expertise, developing civilian defense ministry capacity, and building civil society monitoring capabilities would enhance civilian authority and accountability in civil-military relations.

Generational Change

As military officers without New Order experience assume leadership positions, opportunities emerge for transforming civil-military relations culture. Younger officers educated in democratic environments may more readily accept civilian supremacy and professional military roles. However, institutional cultures change slowly, requiring continued emphasis on professional education and democratic values.

Addressing Persistent Challenges

Papua, military business interests, accountability for past violations, and territorial command roles remain persistent challenges in Indonesian civil-military relations. Addressing these issues requires political courage, sustained reform commitment, and willingness to confront military resistance. Progress on these fronts would significantly advance democratic consolidation and civilian control.

Conclusion

Civil-military relations in Indonesia represent an ongoing journey from military-dominated governance toward democratic civilian control. The nation’s experience offers valuable lessons about the challenges of reforming entrenched military political roles, the importance of addressing economic dimensions of military power, and the necessity of sustained commitment to institutional transformation.

From the revolutionary origins that shaped military political involvement, through the New Order’s extreme military dominance, to post-1998 reforms that achieved significant but incomplete progress, Indonesian civil-military relations demonstrate both the possibilities and difficulties of democratic transition. Real stories like the Petrus killings, the Aceh peace process, and ongoing challenges in Papua illustrate the human consequences of civil-military relations dynamics and the importance of establishing effective civilian control.

As Indonesia continues consolidating its democracy, further progress in civil-military relations remains essential. Completing institutional reforms, building civilian capacity, addressing accountability gaps, and transforming military culture will determine whether Indonesia achieves fully democratic civil-military relations that serve national interests while respecting civilian supremacy. The insights and lessons from Indonesia’s experience provide valuable guidance for this ongoing journey and for other nations navigating similar transitions.

Sharpen Your Skills: Delve into Our Expertise on Politic

Check Out Our Latest Piece on Conflict Resolution: Strategies for Peace in Indonesia!